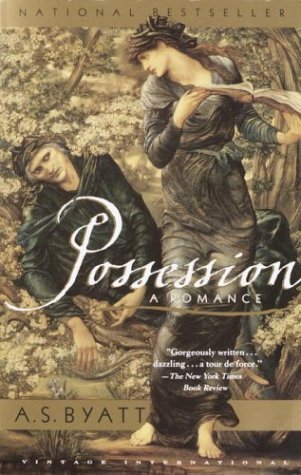

There are certain books that have things happening at different times and a great deal of what gives them their appeal is the way they fit together. I’ve written about a couple of them here before, The Anubis Gates and Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency. All of the books like this I can think of involve time travel except for A.S. Byatt’s Possession. Possession is an odd book, and I love it and re-read it frequently. It’s about scholars in 1987 trying to find out some precise events that happened in the late nineteenth century and which concern the relationship between two poets. But what it’s really about is the way we are what time has made of us, whether we know it or not, the way we exist in our time and place and circumstances and would be different in any other. The way it does this, the very precise way in which the theme is worked out in all the curlicues of the story, makes the experience of reading it more like reading SF than like a mainstream work.

Of course, it’s trivially easy to argue that it’s fantasy. The book contains a number of fantasy stories, or more precisely folk and fairy tales. But the feel of it is anything but fantastical. It’s not at all like fantasy to read. It’s like hard SF where the science is literary history.

Roland Mitchell, a young researcher, finds a draft of a letter by the Victorian poet Randolph Henry Ash. It feels urgent and important, and the book is his quest to follow that clue through all sorts of places nobody has been looking to find out what followed that letter, and having discovered that, to become himself a poet. In addition, the book has passages from Ash’s poems, passages from the poems and stories of Christabel La Motte, the other party in the correspondence, the correspondence itself, journals, memoirs, and lengthy passages that appear to be digressions but are not, about the research methods of Mortimer Cropper, Ash’s obsessed American biographer, and James Blackadder, his British editor. As well as all that, the book is about feminism—Victorian feminism, with La Motte, and modern day feminism with La Motte’s British and American defenders, Maud and Leonora. There are jokes about post-modernism, there are reflections on irony and sexuality, there’s a quest, and two love stories. It’s also wonderfully detailed, I mean it’s full of wonderful details of a kind nobody could make up, and because of the way it connects things up it positively invites you to connect them up and make your own pattern. I’ve probably left things out. It’s a big book and there’s a lot in it.

“I don’t quite like it. There’s something unnaturally determined about it. Daemonic. I feel they have taken me over.”

“One always feels like that about one’s ancestors. Even very humble ones, if one has the luck to know them.”

What keeps me coming back to it, apart from my desire to hang out with the characters, is the way the story fits together and the way it reaches backwards into time. James Morrow said at Boreal last year that when he was writing The Last Witchfinder he realised that you could write going backwards into history in the same way you can going forwards into the future. The first thing I thought of was Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle, and the next thing I thought of was Possession. These books lean back into the weight of time with the perspective of distance and do things with it.

I mentioned it has the letters, the wonderful vibrant conversation of two poets. It would be worth reading just for that. It also has some very well-faked Victorian poetry, some of it actually good. And it has a description of reading, though not as astonishing a one as Delany’s in Stars in My Pocket. It’s one of the most intricate books I own, and I recommend it to anyone who can bear description and doesn’t require explosions.